The Antikythera Surface Survey is an interdisciplinary research project carried out in collaboration with the following institutions:

- Trent University, Canada

- University College London (UCL), United Kingdom

- Hellenic Archaeological Service (6th Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities)

and performed under the auspices of Canadian Institute in Greece and the Ministry of Culture.

Summary information about the survey and the results as presented by the Andrew Bevan (UCL), James Conolly (Trent) in collaboration with Aris Tsaravopoulos (KSF EPCA) on the website: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/asp/el/intro.shtml.

More information about the research (The Antikythera Survey Project) can be found on the website: https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archives/view/antikythera_ahrc_2012/

Surface Survey of Antikythera

The Antikythera Surface Survey was a multidisciplinary research project involving multiple stages, including field research, material study, and laboratory analyses. The project aimed to investigate the long-term history and human ecology of this tiny Greek island. The research project lasted from 2005 to 2008, the material study conferences were completed in 2010, and the complete series of publications of our findings is now available. Please see below and the following pages of this website for more information.

Antikythira is one of the smallest (approximately 20 square kilometers) and most remote inhabited areas in the Mediterranean islands. At the same time, it is one of the best located, at the crossroads of sea routes, with the north-south axis connecting the southern Balkans (Peloponnese) with Crete and the east-west axis connecting the eastern and central Mediterranean. This strategic, but often fragile and marginal position is characterized by the presence of a fortified pirate community during the Hellenistic period (4th to 1st century BC), as well as a shipwreck found a few hundred meters from the mainland and dating back to the 1st century BC. A series of bronze statues came from this shipwreck, as well as the well-known Antikythera mechanism, a complex device for maritime navigation.

Antikythera offers extremely favorable research conditions for three main reasons:

- Small islands tend to be marked by sudden population changes, as well as periods of total abandonment and resettlement. Indeed, our findings show that Antikythera has a long and turbulent past. It begins at the end of the Late Neolithic period and is characterized by a significant human presence during the Bronze Age, a fortified city during the Hellenistic period, social groups during the Roman period, Byzantine and Venetian elements, and a recent episode of resettlement. In addition to some sharp increases in population, there have also been significant decreases in the number of inhabitants, especially in the last hundred years. This relatively uneven presence of human activity facilitates the dating and understanding of settlement strategies and multiple cycles of investment in the landscape (e.g., terraces) in relation to other Mediterranean landscapes.

- Small islands, such as Antikythira, can play idiosyncratic but also revealing roles within broader social, economic, and political networks (for example, as places of refuge for refugees, hunters, political exiles, hermits, monks, and/or pirates). Through the EEA, we have been able to study many of these phenomena by combining different types of environmental, archaeological, and historical data and placing them within the broader Mediterranean context from which they originate.

- Antikythera is small enough to allow for intensive surface research across its entire area, as well as the collection of further data. Despite the successful implementation of high-resolution archaeological and environmental research on several Aegean islands, such as Kythira, Milos, Kea, and Crete, these research projects were necessarily limited to sampling the wider area for the collection of material. In contrast, in Antikythira, we were able to collect information from across the entire island, thus allowing for a greater variety of analyses.

Research Methods

Our knowledge of the island's long-term history is expanded with the help of at least six interdisciplinary methods:

- Walking

- Reflection on the canvas

- Geoarchaeology

- Ceramic Petrography

- Ecological Modeling

- Spatial Analysis

Results

The results of the survey are presented here as a brief report.

Distribution of Settlements

Outlining the history of human exploitation in Antikythira is the primary research objective of the EEA, and we are able to present here some initial observations based on the first phase of studying the material from the surface survey.

The earliest traces of human activity on the island date back to the Late and Final Neolithic periods (5th to 4th millennium BC) and include diagnostic arrowheads, as well as very small (less than 0.25 hectares) concentrations of flint and obsidian finds. Small quantities of pottery dating to the Final Neolithic and the first phase of the Early Bronze Age are associated with many of these concentrations (while some worked stone finds suggest an earlier Late Neolithic phase for which no pottery has been found), and we believe that the earliest stages of this activity constituted a non-permanent presence of hunters from Crete or Kythira. The target of these groups may have been migratory birds (perhaps using nets) as well as native or introduced deer and/or goats, most likely using arrows. We suspect that there is an interesting series of correlations between these early sites and their ecological environment—many are located in easily accessible places, sometimes on possible routes across the island, sometimes with better visibility of the surrounding area and/or access to standing water. Each of these factors needs further investigation to be confirmed. Nevertheless, such a land use distribution may have existed even at the beginning of the 3rd millennium BC, and the island may have been permanently inhabited after the neighboring Kythira and Western Crete.

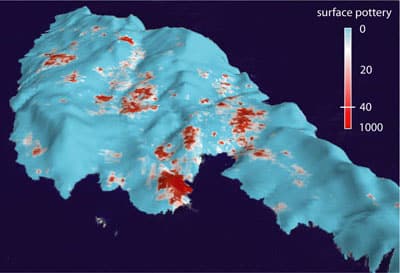

The dating of the first appearance of a more permanent settlement with a different configuration cannot be determined with accuracy without further study. It may have emerged during the second phase of the Early Bronze Age (approximately 2900-200 BC) or immediately thereafter. It is certain that it was already established during the first palatial period (c. 1900-1750 BC) and was maintained during the second and third palatial periods (c. 1750-1450 and 1450-1200 BC). These concentrations from the Minoan and Mycenaean palatial periods are larger (usually 0.25-0.5 hectares), relatively dense, and consist of material suggesting the existence of permanent family farmsteads (with sporadic variations, which means that our final interpretations may need to be more detailed). We have recorded 25 to 30 such concentrations, scattered in sparser groups consisting of two or more separate concentrations (see Figure 5). In any case, they are located in areas of the island with the most arable land, and it seems that the people who lived here exploited specific soils and topographical features, such as sinkholes filled with flysch or marly alluvial deposits in shallow channels that could be built with terraces to retain soil and moisture. In this case, too, further analysis is needed to confirm or refute these hypotheses.

The next chronological phase with clear signs of habitation is observed about a millennium later, particularly during the Hellenistic period (approximately 323-146 BC) when the island was dominated by a fortified city (covering an area of approximately 7 hectares), which was strategically located on the north coast and controlled the natural, protected harbor of Xeropotamos. Ancient sources refer to the city and the island as Aegila and mention their pirate activity. It is true that the city is not particularly close to the best agricultural land on the island, but on the contrary, it is well positioned to have access to the busy Hellenistic sea routes between the Peloponnese and Crete, and east-west between the Aegean and the central Mediterranean. Our research has revealed the presence of other Hellenistic settlements on the island, and their study will highlight whether they constitute smaller rural social groups or belong to the administrative and economic structure of the fortified city. The sacking of the city by the Romans in about 64 BC caused a dramatic decline in their activity, and we do not find other similar quantities of surface material in the area until the Late Roman period (about 5th-7th century AD).Four to five denser concentrations of material date from this period, often accompanied by small groups of box-shaped tombs from the same period. Each concentration of material is located in the middle of one of the most arable areas of the island. Most appear to be small, consisting of a few families at most, except for the one located above present-day Zampetiana, which may be a larger social group. Some Late Roman finds from the port of Xeropotamos suggest that it remained important during this period. However, it is possible that the importance of the port at Potamos was growing, especially considering that the use of the port at Xeropotamos was becoming increasingly difficult due to a combination of tectonic uplifts and alluvial deposits.

View of the historical settlements near Katsaneviana: Prehistoric pottery is depicted in red (from the collection of pots) and orange (from the march), while the worked fragments of obsidian and flint are depicted in black and white, respectively. The two dispersions in front appear to be two Minoan farmsteads from the palatial period. Image: A. Bevan.

A discontinuity in the distribution of settlements on the island is observed during the following two centuries, followed by a new period of exploitation in the 12th century AD. Interesting material dating from this period has been found at various locations on the island. In this case too, the study of the material is at an early stage, but few finds have been identified for the subsequent chronological phases, which suggests mild activity (and perhaps little or no habitation) until the documented repopulation of the island in the 18th century AD. This last chapter in the island's history is characterized by intense activity: at least in the social memory, it began with a relatively small episode of settlement by a few families on the island, who came from the wider area of Chania in western Crete. Growth was recorded as a result of domestic population increase and further population influx to the island during the 19th century. There were now up to ten small settlements, each consisting of a few houses, which usually took the name of the founding family. The associated contemporary pottery is scattered extensively across the landscape, but shows interesting functional differentiation, with some of the tableware being found more frequently around houses. The population began to decline in the 20th century, falling rapidly after World War II, so that today it does not exceed 30 inhabitants during the winter months. In a way, we would like to see if the social and economic conditions of recent colonization and prosperity over the last two centuries, and decline, can provide us with some information about other population changes and land use patterns on the island in the past, or whether, on the contrary, they reflect atypical, historically unforeseen factors.

We can say that, on a larger scale, there are some limited areas with more fertile soils on the island, which have repeatedly been targeted for exploitation. Despite their small size, the Antikythera Islands raise interesting questions about the reuse of various forms of capital investment within the landscape. On a smaller scale, it is possible to identify differences in terms of living and communication strategies. Furthermore, capital investments such as the construction of terraces show reuse which, based on our initial chronological observations, seems to go through certain phases of abandonment. Similarly, at the level of individual settlements or areas of activity, we sometimes observe traces of distinct phases of activity, separated by long intervals of time, suggesting that certain points in the landscape acquired a stronger sense of space, even though often the only thing that makes them stand out are the remains of past activity.

Prehistoric Pottery

A wide range of prehistoric pottery was found during the EEA's survey and collection of pottery shards. This material poses a challenge for two reasons: a) it consists mainly of coarse pottery without decoration, and b) there is no excavated prehistoric site on the island with a clear chronological sequence on which to base our analyses. We must therefore understand and date the finds by developing a typology of coarse pottery based on detailed macroscopic observation., petrographic analysis, comparisons with better established sequences from neighboring areas, such as Kythira and western Crete, as well as paying particular attention to variations within the dispersions on the island (for the increasing importance of such approaches in the southwestern Aegean and beyond, see Moody et al. 2003: 39-44; Kiriatzi 2003: 124-126). Lindsay Spencer and Andrew Bevan (UCL) studied the material macroscopically and then Virtue Pentadec and the Evangelia Kyriatzis (Fitz Workshop, British School of Athens). carried out the petrographic analysis. Further analyses are expected. We will then refer to some preliminary results.

Chronology and Schemes

The earliest dated shell found on the island is a perforated vessel from the Late Neolithic period (see image on the right), but there are indications of significant activity on the island during the Late Neolithic to Early Bronze Age I, such as a characteristic ceramic material with flint (also found in the earliest layers of deposits at Kastri in Kythira), some thick bases from deep wide-mouthed vessels and perhaps some sherds with pottery mixed with calcite. There is a large amount of material from the Early Bronze Age II, which includes a well-preserved section of a sauce boat (see image on the right), characteristic types of inverted rims of deep wide-mouthed vessels, and impressed decoration with a fishbone pattern. In general, this early pottery complements the weathered stone finds and together they indicate significant activity on the island during these periods (the polished stone finds also indicate an earlier, Late Neolithic phase of exploitation).

In Antikythira, there is also early Minoan pottery and material dating to the First Palace period (approximately Early Minoan I – Middle Minoan II). So far, only one diagnostic sherd—a thin ceramic cup with an angled rim—can be dated with certainty to the Early Palace period, but a series of indications suggest that these phases are strongly represented on the island, despite the difficulty in locating characteristic diagnostic material. For example, there is evidence of imported Kythirian pottery mixed with sand, pottery mixed with Cretan-style calcite, and thin, oval-shaped legs from tripod pots. All of these are very often associated with assemblages from the Early Minoan and First Palace periods in neighboring areas. Further study of the material is needed, but even at this stage, the evidence from its spatial distribution highlights interesting settlement changes during this period in relation to previous ones (Late Neolithic to Early Bronze Age II).

As regards the subsequent Second Palace period (Middle Minoan III to Late Minoan I), there are clearer indications of significant settlement activity on Antikythera. This is suggested by the imported Kythirian pottery, characteristic of the Second Palace period, as well as by the possible local production of pottery similar to Kythirian, such as deep wide-mouthed vessels, tripod cauldrons, and various small vessels of fine pottery, such as Vapheio bowls and conical bowls. There is also sufficient material from the Third Palace period (Mycenaean), with at least eight tall legs from cups (many with a characteristic hole in the upper part of the leg that was created before firing), some rims from characteristic triangular deep wide-mouthed vessels and pithoi with plastic incised decoration, characteristic of the Chania region in western Crete.

Macroscopic and petrographic analysis have begun to shed light on the landscape in terms of imported pottery and locally produced pottery. Imported pottery suggests regular communication between Antikythera, Kythira, and western Crete, while there are also indications of the transfer of specific pottery production traditions between these regions. The practice of using sand as an admixture is considered common in Central and perhaps Western Crete. Although it appears that (local?) pottery with angular sand admixture follows a similar clay processing tradition, geological sampling and replica construction are needed to confirm these assumptions.

The use of different mixtures for handles, legs from tripod cauldrons, and plastic decorative bands is found in this rather local pottery, but is also associated with Crete and Kythira. At the same time, a special category of conical deep wide-mouthed vessels with incised and impressed decoration on the inside is very common in Antikythira and seems to be related to western Crete (Christakis 2005: 19, while it is absent from the pottery assemblages of Kythira further north). Finally, the use of a handle that is «nailed» into the wall of the vessel is also known in Crete and Kythira and appears in the local pottery of Antikythira. Another interesting feature is the discovery of two disc-shaped spindle whorls in Antikythira, which indicate knowledge of specific Cretan weaving practices and the fact that the transmission of technology was not limited to the production of pottery.

Ceramic Material Groups

The ceramic material we encounter most often contains angular sand impurities: according to our research so far, this seems to be consistent with the island's geology and probably indicates local production. Some other ceramic materials mixed with flint, crushed pottery, siltstone, and/or calcite could possibly be produced locally, although they are compatible with the geology and ceramic material recipes of neighboring areas. More study of the material is needed before we can draw any clearer conclusions.

Some ceramic materials are undoubtedly imported, such as those containing sand, siltstone, or mica, which have been found in Kythira, north of Antikythira (see Kiriatzi 2003, Broodbank and Kiriatzi 2007: 249-6, Broodbank et al. 2005). Others, such as pottery with phyllite admixtures, and perhaps the denser pottery with calcite admixtures, closely resemble those recorded in western Crete (see Chandler 2001, Moody 1985, Moody et al. 2003) and may originate from there.

An initial assumption we could make is that half, if not more, of the prehistoric pottery was imported to the island. This should come as no surprise, especially when one considers the relative lack of good local clay sources and the relatively small population that the island could support. In some later chronological phases, and perhaps in some prehistoric phases as well, it is possible that no pottery was produced on the island at all. A further geological survey is being carried out to narrow down the range of possible sources that would have been accessible to the Antikytherian potter (for impurities, clay, etc.).

Bibliography

Broodbank, C. and E. Kiriatzi 2007 ‘The First “Minoans” of Kythera Revisited: Technology, Demography, and Landscape in the Prepalatial Aegean’, American Journal of Archaeology 111: 241-74.

Broodbank, C., Kiriatzi, E., and J.B. Rutter 2005 ‘From Pharaoh’s Feet to the Slave-Women of Pylos? The History and Cultural Dynamics of Kythera in the Third Palace Period’ in A. Dakouri-Hild and E. S. Sherratt (eds) Ace High: Studies Presented to Oliver Dickinson on the Occasion of His Retirement: 70-96. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Chandler, G.M. 2001 ‘Comparative Petrographic Analysis of Sherds from five Minoan Sites in Western Crete’, in Y. Bassiakos, E. Aloupi and Y. Facorellis (eds.) Archaeometry Issues in Greek Prehistory and Antiquity: 379-396. Athens: Hellenic Society of Archaeometry and Society of Messenian Archaeological Studies.

Christakis, K. 2005 Cretan Bronze Age Pithoi: Traditions and Trends in the Production and Consumption of Storage Containers in Bronze Age Crete, Philadelphia: INSTAP Academic Press.

Kiriatzi, E. 2003 ‘Sherds, Fabrics and Clay Source: Reconstructing the Ceramic Landscapes of Prehistoric Kythera’, in K. Foster and R. Laffineur (eds.), Metron: Measuring the Aegean Bronze Age. (Aegaeum 24): 123-29. University of Liège. Liège.

Moody, J. 1985 ‘The Development of a Bronze Age Coarse Ware Chronology for the Khania Area of West Crete’, Temple University Aegean Symposium 10: 51-65.

Moody, J., Lewis, H., Robinson, J. Francis, and L. Nixon 2003 ‘Ceramic fabric analysis and survey archaeology: The Sphakia Survey’, Annual of the British School at Athens 98: 37-105.

Classical-Roman Pottery

The most impressive archaeological site on the island is the fortified Hellenistic city, known as Kastro. The city covers an area of approximately 7 hectares, and the pottery and coins found within the site date it to the late 4th to mid-1st century BC. Both the city and the island were probably known as Aegilia during the Classical to Roman period. In fact, ancient sources refer to Hellenistic Aegila as a pirate community whose activities led to several military expeditions, such as the attack by the Rhodian fleet in the 3rd century BC and the final sacking of the city by the Roman fleet in 69-67 BC. Annual excavations are carried out at the castle (a separate project directed by the Greek partner of the EEA, Aris Tsaravopoulos, see Martis et al. 2006) have brought to light multiple phases of fortifications, a neosiko carved into the rock, a temple dedicated to Apollo at the port of Xeropotamos, and archaeological and epigraphic finds that highlight the broader cultural, economic, and political relations of Aegila (see also Martis et al. 2006).

The EEA's surface survey of the wider island landscape revealed a more extensive distribution of Hellenistic material at various sites, but as far as the Classical and Roman periods are concerned, there is little clear evidence of significant activity (although the study is still in its early stages). Alan Johnston (UCL) will study this material in the spring of 2008 in order to better clarify this apparent discontinuity and investigate the nature of the Hellenistic presence in the wider landscape, particularly in relation to the more well-known activities of the Kastrou community.

With the end of the Castle community, there is minimal material from the later Roman period (further study of the EEA material for this period is expected). However, excavations carried out as part of a separate project directed by Aris Tsaravopoulos (see Pyrrou et al. 2006) brought to light box-shaped tombs dating from the 5th-7th century AD. The tombs are complemented by the findings of surface research, which indicates the existence of abundant Late Roman pottery on the island, in the form of a low-density dispersion in the most fertile parts of the island. Another six or so denser dispersions are likely to be small, permanent communities that consumed and discarded an interesting range of pottery, such as coarse pottery, storage vessels with comb-incised decoration, painted tableware, and glass. These distributions are expected to be explored more intensively during the study.

Bibliography

Martis, T. and Zoitopoulos, M. and A. Tsaravopoulos 2006 ‘Antikythera. The Early Hellenistic Cemetery of a Pirate’s Town’, in S. A. Luca and V. Sîrbu (eds.) The Society of the Living – the Community of the Dead (from Neolithic to the Christian Era). Proceedings of the 7th International Colloquium on Funerary Archaeology: 125-134. Sibiu: Bibliotheca Septemcastrensis. (full text, 15.8 MB pdf)

Pyrrou, N., Tsaravopoulos, A. and C. O. Bojica 2006 ‘The Byzantine Settlement of Antikythera (Greece) in the 5th-7th Centuries’, in S. A. Luca and V. Sîrbu (eds.) The Society of the Living – the Community of the Dead (from Neolithic to the Christian Era). Proceedings of the 7th International Colloquium on Funerary Archaeology: 224-236. Sibiu: Bibliotheca Septemcastrensis. (full text, 15.8 MB pdf)

Medieval – Modern Pottery

The study of Medieval to Modern Pottery of the EEA has been undertaken by Joanita Vroom (Sheffield). Her research work to date has contributed significantly to highlighting the academic profile and analytical importance of these later phases of material culture in the Eastern Mediterranean.

The study of the total pottery of Antikythera is expected to be completed in 2008, but the preliminary results are already interesting: ceramic assemblages from the 5th-7th centuries are abundant on the island, while diagnostic pottery from the 8th-11th centuries is scarce. In contrast, finds from the 12th-13th centuries have been found at several sites and include glazed fine pottery, amphorae, and coarse pottery.

Although the scarcity of pottery indicates limited exploitation of the island's natural resources during the centuries that followed (particularly during the 15th-16th centuries), the next period of prosperity, based on pottery, dates from the end of the 18th to the beginning of the 20th century AD. According to historical records, this phase began with the resettlement of certain families on the island, who came from the wider area of Chania in western Crete. This final phase of pottery consumption is responsible for the widespread distribution of material throughout the island. As a result, it allows us to explore the differences in pottery consumption between various Antikythira households, the spatial and functional relationships with other buildings and agricultural facilities, as well as evidence of trade outside the island and/or domestic pottery production. Vroom also studies the pottery from the surface survey in neighboring Kythira. The combination of this study with the observations based on the material from Antikythera and the current ethnoarchaeological research of Evangelia Kyriatzis , based on production techniques and sources of raw materials in present-day Kythira, promises new perspectives for investigating the distribution of pottery production and consumption at the regional level in the southwestern Aegean.

Stone Objects

Almost two thousand worked stone finds were collected during the survey and collection of pottery. It is noteworthy that tripartite tools such as millstones are rare, despite our intensive efforts to locate them. The geology of Antikythera is characterized entirely by limestone, which rules out the existence of any good local source of material for the manufacture of such tools, and probably as a result they were preserved.

In contrast, the collection of flaked stones is much more impressive. The earliest material probably dates to the Late Neolithic and includes triangular arrowheads and flaked micro-cores. Material from the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age is abundant and includes a series of prismatic blades, blade cores, and serrated arrowheads. Some of these finds have been found in association with Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age pottery, suggesting more extensive or repeated episodes of occupation. However, many are located in areas less suitable for agriculture, raising questions about the seasonality, permanence, and function of early human activity on the island. In the same context, we could also take into account the impressive number of arrowheads, which probably indicates the island's appeal to hunters. The local white flint was used relatively systematically for the manufacture of an extensive range of tools, including arrows, but at the same time, an unexpected quantity of obsidian from Milos has been found, which includes a large core of Early Bronze Age blades and many arrowheads. Evidence of the use of polished stone tools during the Middle and Late Bronze Age is more limited.

Terraces and Other Landscape Investments

A distinctive feature of Mediterranean landscapes is the fields, roads, and terraces, which often constitute complex and extensive systems. They are long-term, non-automatic investments (sometimes referred to as ‘landesque’ capital), which are usually used for many generations (one could say that the same is true of some of the most long-lived orchards).

Despite their obvious importance in the past and their clear relevance to current concerns about sustainable agriculture, the social context in which these structures emerged is not fully understood. Common explanations for the emergence of terraces, for example, cite population pressure, increasing expansionist tendencies, and the need to improve productivity by farming more marginal and sloping areas. As part of an autonomous subprogram in Antikythira, funded by the Landscape and Environment Research Program of the Arts and Humanities Research Council of the United Kingdom, We have investigated these issues in greater detail, combining archaeological and geoarchaeological surveys, ethnographic research, and statistical analysis.

Many of the analytical problems associated with understanding the relationship between landscape modifications, such as terraces, are less pronounced in Antikythera due to its sporadic settlement history, which facilitates the correlation of terrace construction with specific phases of the past. We attempt to understand these elements by combining five interrelated approaches:

- Complete digital mapping of the terraces on the island, based on modern Quickbird satellite images, aerial photographs from 1944, when the island's terraces were still in use, and an extensive field study program. This dataset is accessible from the website downloads and, to our knowledge, it is one of the few data sets of this type in the Mediterranean.

- Geoarchaeological overview of key areas where we could uncover multiple terraced phases, focusing on their construction techniques, erosion episodes, and variations in soil fertility.

- Thorough archaeological research provides us with a picture of the pottery associated with these structures and allows us to isolate parts of the landscape that may have relatively simple terraced phases worthy of further study.

- Ecological modeling of the island's vegetation and how it relates to large human investments. Particular attention is paid to identifying crop residues on the most abandoned terraces, understanding the process of their recolonization by wild vegetation, and the effect of erosion.

- Ethnohistorical research through interviews with the oldest remaining residents of the island and study of extensive historical archives from the 18th-20th centuries on Antikythera. These methods aim to understand when and how the terraces were built, who owned them, what was cultivated on them, and what effect the various phases of terrace construction had on the overall fertility of the island.

The mapping of all terraces has been completed (a final field study will be carried out in spring 2008) and it is estimated that there are approximately 12,000 such structures on the island. The most extensive period of construction and use is probably the most recent, with significant activity throughout the 19th century. However, stratified soils in several areas indicate the existence of earlier episodes, from the Roman period, but also from the Bronze Age, if we take into account the associated pottery. An Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) dating program is being prepared for the spring, as well as radiocarbon dating, in order to confirm and develop these observations.

There are also clear correlations between geological rock types and soil types and the tendency to build terraces, with greater investment in areas with Neogene marl limestone formations. Similarly, there are several important examples of terraces that exploit the leeward side of large fault zones, where the cliff faces provide protection from sea winds and create microclimates with more rainfall. The terraces and related investments attracted populations even in times when the island was almost deserted: more specifically, it seems that new settlers returned to areas with previous human presence (i.e., areas where there were visible damaged and abandoned terraces, etc.) to an extent that exceeds what one would expect if there were simply a preference for wider environmental zones. In other words, such remains create the impression of a structured area, which is of enormous importance for their long-term role.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Greek Ministry of Culture for granting us a research permit, as well as our main external funders, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, the Arts and Humanities Research Council of the United Kingdom, the Institute of Aegean Prehistory and the Mediterranean Archaeological Fund. Also, the Institute of Archaeology, University College London provided financial support to address shortfalls in other funding programs. Our commissioner in Athens was Canadian Institute in Greece . We are grateful for the support he has given us and would like to thank the deputy director in particular. Jonathan Tomlinson for his regular contributions. This program benefited from the opportunities created through an official collaboration (with Aris Tsaravopoulos as the Greek partner). All three of us would like to thank the 6th Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities for their continued support. We would also like to thank 1st Ephorate of Byzantine Antiquities and especially Marina Papadimitriou for her help with various issues.

Two of us (AB and JC) have benefited greatly from our participation in the largest surface survey conducted on the neighboring island of Kythira, as part of the Kythira Research Program (under the direction of Cyprian Broodbank and Evangelia KyriatzisOur contribution continues as the program approaches its final stage of publication. In addition, the following individuals provided important advice or academic support during the years 2005-7: Ted Banning, John Bennet, John Cherry, Jack Davis, Jennifer Moody, Lucia Nixon and Todd Whitelaw.

We would like to express our heartfelt thanks to the current residents of Antikythera for their generosity, assistance, and warm hospitality, especially Andreas Charhalakis, Manolis Charhalakis, Nikitas Galanis, Evangelos Kalkanakos, Georgios Katsanevakis, Maria Katsanevaki, Marinos Katsanevakis, Myronas Patakakis, Dionysios Progoulakis, and Myronas Progoulakis. During the fieldwork, three different doctors worked on the island and provided us with significant support.

The content of this website is the result of the work of many people, each of whom is mentioned separately on the relevant web pages. It was designed by the research project managers, but Greg Hives and Anna Stellatou also provided significant support. Finally, we would like to thank all the people who contributed to the fieldwork and material study (complete staff list) – we realize the thorny and/or dusty price you often paid for supporting the EEA (for unofficial impressions of the EEA's fieldwork, see video recordings of the members of the EEA).

Andrew Bevan (UCL)

James Conolly (Trend)

Aris Tsaravopoulos (KSF EPCA)

—-

Slide show with photos from the research team