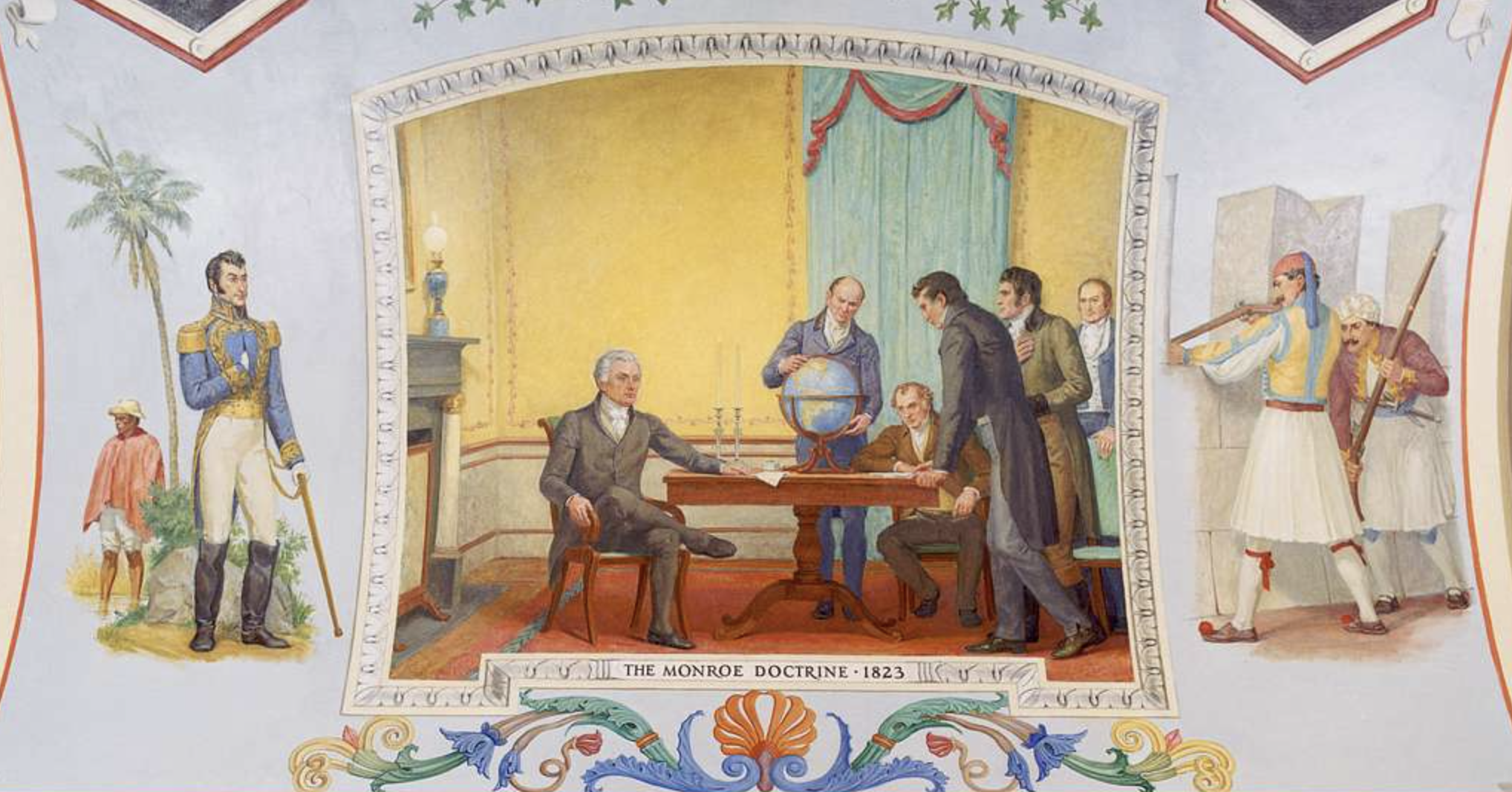

In 1823 not a single shot was fired. No troops moved. No borders were changed.

And yet, in that year one of the most enduring rules of power in modern history was carved out.

With the so-called Monroe Dogma, the United States declared that «America belongs to the Americans». The wording seemed innocent. Almost liberating. An end to European colonialism, a promise that the New World would never again be a field of plunder by old empires.

But history, when it matures, always reveals what the words really meant.

The Monroe Doctrine did not talk about the right of peoples to decide. It spoke of the right of others not to interfere. And in that vacuum, the United States positioned itself as the the natural overseer of an entire continent.

It was not yet an empire.

But it was already an imperial thought.

Latin America was not treated as a set of societies, histories and cultures. It was treated as a space. As a geography to be exploited. As a reserve of raw materials, markets, ports, cheap labor. And this space, according to the new doctrine, had to remain open, not to its peoples, but to interests.

For decades, the Monroe Doctrine has looked more like an ambition than an implemented policy. The US did not yet have the power to impose itself openly. But the direction had already been set. And when the power came, the action came.

In 1898, with the Spanish-American War, the theory became a reality. Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Caribbean as a whole, became the first laboratory of American imperialism. From there, the Monroe Doctrine ceased to be a declaration and became mechanism.

The 20th century in Latin America was written with this mechanical consistency.

Wherever a government attempted to touch the land, the copper, the oil, where it tried to speak with its own voice, where it dared to challenge the hierarchy, the same rule was activated, it had to be overthrown.

In Guatemala in 1954, an agrarian reform was enough to be considered a threat. In Chile in 1973, the democratic election of Allende protected no one. In Nicaragua, El Salvador, Argentina, Uruguay, democracy was set aside in the name of «stability». Dictatorships were installed, coups

were organized, people disappeared.

The Monroe Doctrine no longer needed to be mentioned. It was already a status quo.

And somewhere in this long history, Venezuela appears.

It cannot be an exception, but a continuation.

When at the beginning of the 21st century Venezuela attempted to control its wealth and establish an independent policy, the old doctrine was immediately reactivated. Not with colonial flags, but with new words, sanctions, «humanitarian crisis», «restoration of democracy».

In 2002, the attempted coup against Hugo Chavez clearly showed that nothing had changed in substance. When it failed, the methods were adapted. The war became economic. The siege became invisible, but just as suffocating.

Venezuela was not punished for authoritarianism. It was punished for disobedience. Because he dared to question the self-evident Monroe Doctrine, that the continent has an owner.

When Donald Trump openly declared in 2019 that the Monroe Doctrine was «coming back», he was simply saying out loud what had been silently applied for decades. It was not a return. It was about confession of continuity.

Venezuela today is where Cuba, Chile and Nicaragua were before it. In the same chain. In the same historical pattern. In the same conflict between self-determination and imperial surveillance.

And here, almost inevitably, Che Guevara returns. Not as an image, not as a symbol of empty content, but as a historical consciousness. Che never spoke about imperialism in the abstract. He experienced it in the interventions, in the subversions, in the puppet governments

Che Guevara is not a thing of the past.

It belongs to every historical moment when a people tries to stand up.

Che identified imperialism as the system that changes faces, but not ends.

When he spoke of the need to name the leader of imperialism, he spoke of historical clarity.

When he said that in order to destroy imperialism, its leader must first be named, he was not making rhetoric. He was making a political statement.

Two centuries after 1823, the Monroe Doctrine is not a thing of the past. It is present. It lives in sanctions, in threats, in «special operations», in words that turn intervention into assistance and submission into salvation.

And as long as this doctrine survives, Latin America will remain a field of conflict, not because its peoples want it, but because they have never ceased to claim the right to decide for themselves.

From the Monroe Dogma to Venezuela, the route is continuous.

And that is why his voice is not silent.

The story is not closed.

It just continues by other means.

Freedom is not given away.

It is conquered.