Henry Kissinger's dirty role across the globe was perhaps what the US needed in the second half of the 20th century. This role was perfectly served by then-Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, whose intelligence, knowledge, and lack of moral inhibitions combined perfectly with cynicism to build the US foreign policy of the time and his own name.

His name has been associated with American politics long before he took over the State Department in 1973, such as in 1965 and 1966 when he visited Vietnam as an advisor.

And his involvement in the Cyprus issue seems to have begun in 1964. Long before his statement that there is no reason why Turkey should not occupy one third of Cyprus.

“There is no American reason why the Turks should not have one-third of Cyprus.” Henry #Kissinger to President Ford (August 13, 1974). The second phase of the Turkish invasion of #Cyprus took place a day after (August 14-16, 1974). #ItsAnOccupation #CyProb #JustFacts #EastMed #USA #NATO #Turkey pic.twitter.com/19VCep2BCZ

— Euripides L Evriviades 🇨🇾🇪🇺 (@eevriviades) September 2, 2018

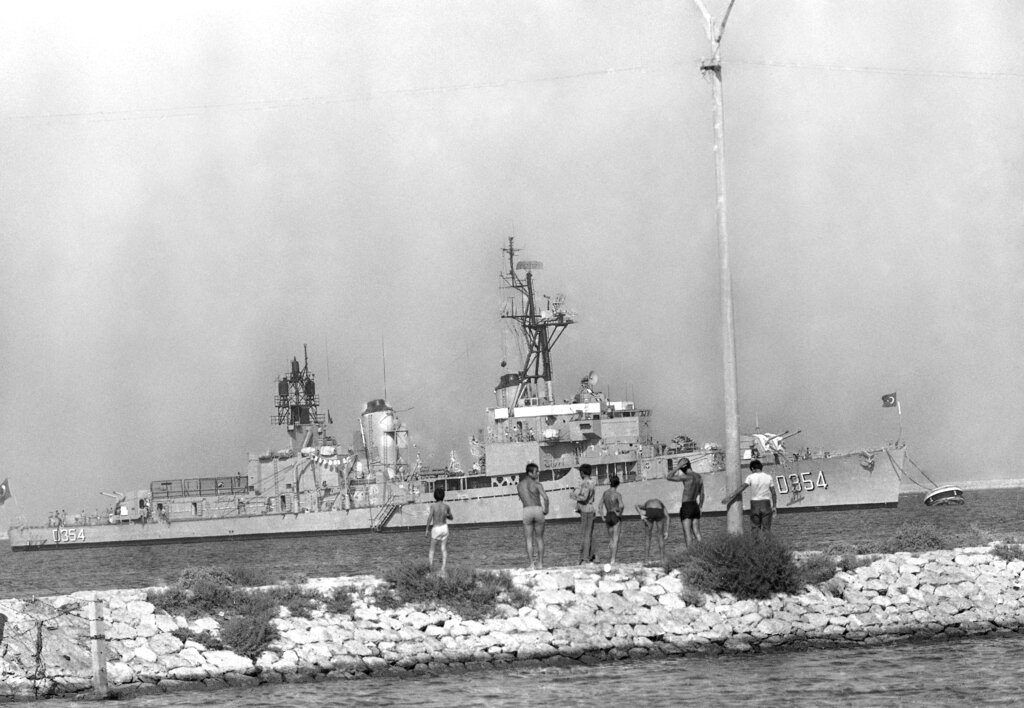

It certainly culminated shortly before the Turkish invasion of Cyprus, when the American ambassador in Athens, Henry Tasca, was informed of the Turkish preparations, sent an urgent telegram to Kissinger asking him to move the 6th Fleet between Turkey and Cyprus to prevent the landing. Kissinger was furious. «Stop being so emotional about the Greeks!» he replied. The KYP (Cyprus Intelligence Service) reported from Nicosia that the Turkish fleet was sailing south towards Cyprus, but Athens reassured everyone: «Don't listen to what they say, the Turks won't invade, they're just conducting exercises...»

Let's not repeat 1964

Apparently, as everything indicates, Henry Kissinger left the matter to his deputy Joseph Sisco, pulling the strings from behind the scenes, not wanting a repeat of 1964 when the then Prime Minister of Turkey was preparing to send his troops to Kyrenia. Lyndon Johnson's angry letter literally saved Cyprus. Ten years later, Sisco undertook a similar mission, without having anything in his briefcase. He didn't even have instructions from his boss... And it was no coincidence, since Turkey was setting conditions that no Greek government could accept, which would allow it to invade Cyprus.

With the opening of State Department archives, Kissinger's role in relation to Hellenism was revealed. He «lulled» President Nixon with his supposed concerns that Makarios would turn to communism and the Eastern Bloc, and suggested that the US stay away from Cyprus!

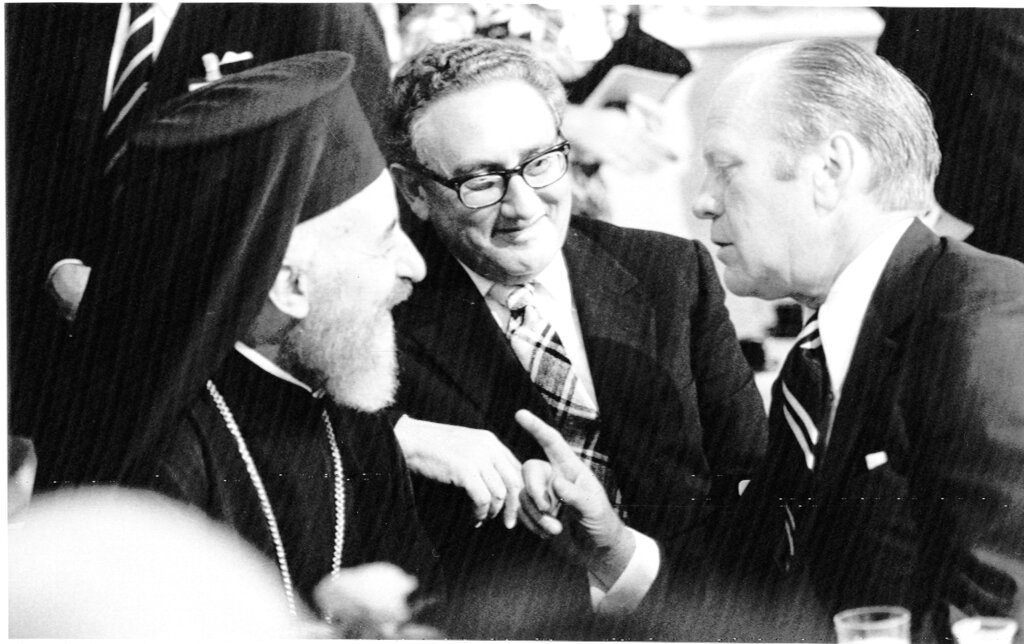

Just how slimy and cynical his attitude toward Makarios was can be seen from the conversation they had when they met in the presence of William Crawford, the US ambassador to Cyprus:

Kissinger: «Your Holiness, I am very happy to welcome you to Washington. I want you to know that we have great respect for you. We feel that you are too big for your island. In fact, if you chose to, you could become President or Prime Minister of Greece... Now, Your Holiness, if you were Secretary General of the Soviet Union, that would create big problems for us, having someone like you as an opponent. Your Holiness, when I am with you, I really feel that I like you...».

Makarios: «Dr. Kissinger, this will only last for about five minutes after we part ways. Isn't that right?». Kissinger's smile froze on his face...

A revealing chapter on the tragic moments of Cyprus

The relevant chapter from «The Secret Files of Kissinger: The Decision to Divide» by journalists Michalis Ignatiou and Kostas Venizelos. The book is based on classified documents from the State Department and the White House, which, to this day, 16 years after the book's publication, have never been refuted:

Shortly before dawn on July 18, 1974, the usually smiling Joseph Sisco (US Assistant Secretary of State), accompanied by eleven of his colleagues, climbed heavily up the steps of the plane provided by Henry Kissinger.

At 02:53 GMT, the plane (operating flight SAM 4127, piloted by Robert D. Peterson) was taxiing at Andrews Air Force Base in Washington. The first stop for the members of the American mission was London, where, incredible as it may seem, Sisco had orders to «listen and talk a little.» His hands were essentially tied, as he was going to express the well-known official American position of «non-intervention» in the internal affairs of Cyprus... A few minutes before takeoff, the American undersecretary had a final telephone conversation with his superior, who was in San Clemente. Kissinger was clear: what mattered most to him was preventing a Greek-Turkish war.

Sisco was accompanied on his mission by the following: Robert Elsworth, Assistant Secretary of Defense (passport number Y1221882), Robert Dillon, Director of the Southern Europe Office (ref. no. X047637), Thomas Boyatt, Director of the Cyprus Office (passport no. X040267), Robert Ockley, member of the Policy Planning Staff (passport no. X027710), Arnold Raffel, Special Advisor to Cisco (ref. no. X027948), Teresa Beech, Personal Secretary to Cisco (ref. no. X073248), Rona Richardson, Cisco's secretary (ref. no. Y890296), Lionel Rosenblatt (ref. no. X078296) and Kay Daley (ref. no. Y077898). Mr. Sisco's security was handled by William Tursso (ref. no. X077898) and Stanley Bielinski (ref. no. X079701), who were in possession of Smith & Wesson revolvers. (Department of State – Limited Official Use – July 18, 1974).

On the plane, this senior official, whose name would become associated with the tragedy of the Cypriot people, was deep in thought. He was thinking about a similar mission he had undertaken in 1964, when he accompanied George Ball to Nicosia. The then Prime Minister of Turkey was preparing to send his troops to Kyrenia. Lyndon Johnson's angry letter literally saved Cyprus. Ten years later, Sisco undertook a similar mission, with nothing in his briefcase. Not even instructions from his superior...

In the last meeting before taking on his mission, he discussed the matter at length with Kissinger over the phone: «After discussing the issue again, examining the situation as it stood at that moment, we finally decided that we had to intervene to prevent any (further) military intervention, this time on the part of Turkey,» Sisco recalls. «I felt that if any restoration (of Makarios) was to take place, it had to be through a peaceful settlement. And the last thing we wanted at that time was a conflict between two friends and NATO allies.» (Interview with Joseph Sisco by the authors).

He had already decided that his mission would not be effective, but he believed that if he «blackmailed» Athens and Ankara, Kissinger and the British would be forced to be more helpful. The danger came from Turkey, so that was where the pressure had to be directed, and in all the meetings that preceded the mission, the conclusion was easy and simple: ’Unfortunately,« Sisco had told Kissinger, »any action by Turkey against Cyprus is legally covered.« (Interview with Joseph Sisco by the authors). At the same meeting, the Deputy Secretary of State felt the need to explain—since he was the only one who knew—the actions of the two previous missions, in 1964 and 1967. He emphatically stressed the fact that these two missions had been supported by the president himself. An American diplomat recalls that Kissinger, although very talkative in other meetings, did not say much in this particular one and avoided making any commitments.

"In 1964, things were clear when Dean Rusk wrote the letter that President Johnson sent to the Turkish prime minister," Sisco said.

"And now things are clear," replied Kissinger.

"Henry, you're sending me on a mission that's doomed to fail," Sisko replied.

"You know I will support you," Kissinger said. (Meeting at the State Department – Testimony of an American diplomat – Interview with Joseph Sisco by the authors).

Sisco asked again about Makarios« fate, because American journalists were bothering him, claiming in their articles that Kissinger had knowledge of the plan to overthrow the Archbishop. »Makarios is the loser« (of the game), the minister told Sisco. »It is essentially impossible to restore him to power, and it doesn't matter anymore.’ Sisco couldn't believe his ears. Kissinger continued: «It's not a question of whether I like Makarios or not, or whether I want Sampson or not. That's not the point. The point is that we don't want a war between Greece and Turkey.».

Sisco himself and the diplomats accompanying him were very concerned about one fact that did not characterize Kissinger. In all other international matters, he took the initiative, gave orders, and participated himself in 99% of the missions. In the case of the Cypriot tragedy, he showed unjustifiable restraint, did not take part in any missions, and instead made sure to stay away. Boyat, who accompanied Sisco, as well as the Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs himself, felt alone and helpless. And in the back of their minds, even before they boarded the plane, the idea that the case was lost had taken hold. We had the following conversation with the head of the Cyprus Department: (Interview with Thomas Boyatt by the authors)

Question: It's strange, but from the very beginning, Sisco believed that his mission was doomed to fail...

Boyat: I agree.

Question: Did you sense it from the beginning, even before you started?;

Boyat: I felt it too. I'll tell you why. If Henry believed there was even a chance of success, if he was determined to fight to prevent the invasion, he would have gone himself. He wouldn't have sent Sisko and us. He sent us out there to fail. To put it bluntly, he sent us out there to die. He sent us on a mission that was predestined to fail. Sisko is right.

Question: Really, you didn't get any help from Kissinger?;

Boyat: No, I didn't see any help.

Question: Ball and Vance also had the personal support of the president. Did you have that?;

Boyat: We didn't have a president... Watergate was at its height. A few days later, Nixon resigned. Kissinger was president.

Question: I will persist. Did it not assist you at all?;

Boyat: No.

Question: Did you at least call Ecevit?;

Boyat: That's a good question. He called Ecevit between 15of and 20of July? I don't know the answer.

Question: On July 20, when Sisco called Kissinger to announce that the invasion was beginning, Kissinger replied that he would contact Ecevit himself.

Boyat: Yes, but if he wanted to stop the invasion, he would have called Ecevit before July 20, not at the last minute.

Question: And I believe that if Ecevit had received a phone call from Kissinger, he would have thought ten times before proceeding with the invasion.

Boyat: Logically, and under normal circumstances, Kissinger would have called his old friend Ecevit and told him, ’I'm sending you Sisco, and please pay attention to what he has to say.".

Question: In his book, Kissinger claims that he sent a written message to Sisco about Ecevit. Why didn't he call Ecevit himself to deliver the message?;

Boyat: I agree, it doesn't make sense. Why didn't he do it on the 16th or 17th of July? Why didn't he call and inform Ecevit that Sisco was his personal envoy... (Interview with Thomas Boyatt by the authors)

Boyat, who speaks for his colleagues, points out:

«We sat there with the entire US intelligence establishment in all its glory, having been deceived by a cowardly Greek brigadier. The disaster I had tried to prevent and avert was becoming a reality like your worst nightmare. Well, it was laughable, of course. Several emergency meetings were held, and Kissinger decided to send Sisco on a mission of shuttle diplomacy to solve the problem. And I had been in Washington long enough and had become cynical enough to know that the moment Kissinger sent Sisco, instead of going himself, it meant that he knew there was no hope and did not want to be identified with someone who had failed. So he sacrificed the deputy secretary and his staff, of which I was a member. I mean, it was a clear bureaucratic signal that there was going to be no victory. And that's how it turned out.» (Interview with Thomas Boyatt by the authors – Also, testimony to Charles Stewart Kennedy)

With this information, and Kissinger's expressed antipathy towards Makarios, whom he had written off since July 15, Sisco arrived at Heathrow Airport with a plan to end the crisis based on the efforts of Bol and Vance. Bülent Ecevit had preceded him. Their goals were completely different. The Turkish prime minister was asking for a «helping hand» from England to restore, by military means, the situation that had existed before the coup. The American deputy secretary of state agreed to Makarios« return and went even further. But he ruled out any military action. Prime Minister Harold Wilson and Foreign Secretary James Callaghan condemned the coup against Makarios, welcomed him back after his exile as president of the Republic of Cyprus, and told Ecevit in no uncertain terms that they had no intention of following his choices.

As soon as he arrived in London, Sisco rushed to the Foreign Office. James Callaghan was waiting for him. The minister, who will always be remembered by Cypriots for his monumental statement that «Turkey will one day become a hostage of Cyprus.» This never happened, and England bears the greatest responsibility for this. The two men talked for an hour. From the outset, the disagreement between the Americans and the British over Makarios became apparent. Kissinger's mandate was to prevent war. The restoration of the Archbishop was not a priority of this mission. Sisco called for coordinated action to prevent Turkish intervention. Callaghan expressed the view that if the US really wanted to restore legitimacy, it should announce its support for Makarios. Sisco had no such instructions and could not take any initiative in this direction. He left the British Foreign Office feeling extremely uneasy, as Callaghan had informed him of Ecevit's decision to follow Greece's example and exercise Turkey's right to intervene. The previous evening, Ecevit had attended a dinner hosted in his honor by Wilson and Callaghan.

After his first meeting with Callaghan, the American undersecretary sent a telegram to Washington. (Department of State, Telegram from Joseph Sisco to Henry Kissinger, July 18, 1974). According to the document, both sides were cautious about the issue of Makarios' return, despite not admitting it directly. According to the minutes of the meeting, London continued to support Makarios' legitimacy and restoration on the island. Callaghan claims in the document that Parliament and public opinion have extremely strong views on this issue and he does not believe that the United Nations' efforts should be delayed. Callaghan agrees that in the long term, Makarios' reinstatement is unlikely to be a factor for stability, as he will be tempted to turn to the East. However, Callaghan argues that public pressure is forcing him to continue supporting Makarios. The British Foreign Secretary added that the Greek government would not do anything without considerable pressure from the Americans.

Carrying out his superior's orders, Sisco emphasized that the United States and Britain must make every effort at the United Nations to prevent Makarios from being legitimized and reinstated, since this would be a violation of the UN Security Council resolutions. Sisco also noted the danger of Makarios being promoted again, thus creating instability once more. Sisco also noted the danger of promoting Makarios again and thus creating instability once more. Sisco added that the US government does not see Sampson «as a permanent fixture.». (Department of State, Telegram from Joseph Sisco to Henry Kissinger, July 18, 1974)

Following prior consultations in Washington, Sisco met with an inexplicably cheerful Ecevit in London. During a long lunch, Sisco listened carefully to the Turkish prime minister's terms. An associate of the US deputy secretary of state noted that Ecevit's arrogance and the extent of his threats were such that Sisco felt repulsed. He was also «burning» with the opium issue, which had preoccupied him all the previous week before the coup.

The meeting between Sisco and Ecevit, which lasted almost four hours, was stormy. The Turkish prime minister arrived in London with his proposals in his luggage. As soon as he met with the American mediator, he handed him a typed page listing six actions that must be taken, as he explained, in order for Turkey not to launch a military operation against Cyprus. The Turkish terms, which surprised Sisco, who was aware of Ecevit's antipathy towards Makarios, were as follows:

First: Greek military forces must leave Cyprus.

Secondly: Nikos Sampson, whom Ankara described as «the sworn enemy of the Turkish nation,» must relinquish power.

Third: Athens must agree to sign an agreement for the creation of a federal state, which would consist of the two communities.

Fourth: To ensure permanent access to the sea at Kyrenia for Turkish forces.

Fifth: Makarios should return to power (!!!), and

Sixth: The UN Peacekeeping Force should take measures to prevent the trafficking of weapons and ammunition in Cyprus.

As soon as he finished reading the terms, Sisco had no doubt that it was only a matter of days before Turkey would invade Cyprus. He told this to the Turkish prime minister, who treated the American envoy with suspicion and arrogance. Ecevit, who until then had not been pressured by Kissinger to refrain from invading Cyprus, warned Sisco not to stand in the way of his plans. He emphasized each word:

Things are very different from 1964. This time we will do it our way, he told the American envoy, who asked Ecevit whether Turkey really wanted Makarios to return, as stipulated in the fifth term. The next day, this clause was removed, as it was something that Turkey did not really want, and Ecevit knew that Ioannidis would reject it outright. (Interview with Joseph Sisco by the authors).

Sisco informed Kissinger of his first meeting with the Turkish prime minister in a memo. He wrote: «Ecevit took a hard line and his comments showed that he was sensitive to the internal situation and pressure in Turkey. He provided schematic support to Makarios and continues to call for the withdrawal of Greek officers. He attaches great importance to «strengthening the Turkish presence in Cyprus and the need for Turkish access to the sea». He agrees that it would be useful to talk further with Sisko in Ankara. (Department of State, Telegram from Joseph Sisco to Henry Kissinger, July 18, 1974)

Ecevit's position on the creation of a federal state was presented by State Department officials at the Airlie House conference in 1972. Sisco remembered that meeting well. He agreed with the position on a federation, as well as with Ecevit's other terms, and hoped that Athens would accept them. His concern stemmed from Ecevit's threat that if the Greeks did not agree, he would intervene without delay. The Turks had been preparing since early 1973, confident that they would be given the opportunity. By February 1974, they had seriously considered the possibility of an invasion and had conducted numerous readiness exercises. Turkey's landing craft—the conclusion of the two men's conversation—were waiting for Ecevit's order to disembark the soldiers they were carrying on the coast of Cyprus. Sisco went to London with orders to listen and found himself in the eye of a storm. (Testimony of an American diplomat to the authors).

From the American embassy, Sisco immediately contacted Kissinger and told him everything. The Secretary of State was calm and did not seem concerned. His envoy, however, was on pins and needles. Sisco recalls:

«After my conversation with Callaghan, I had a long meeting with Ecevit, who happened to be in London that same day. Ecevit described to me his views on resolving the problem through a federal solution. He demanded further concessions. I immediately realized that these were proposals that no Greek government would accept, because it would have to capitulate and surrender completely. I told him what I thought. I told him that I would have to go to Athens. I asked him to give me time to discuss it with them, to see what I could do and what I could achieve. Two days later, when he told me that the order to invade had been given, he reminded me of our conversation in London. He had told me then that he would do what was in Turkey's best interests. Even now, I can still hear those words ringing in my ears. ’This time we will do it our way.« I informed Henry about my conversation with Ecevit and alerted everyone I could in Washington and London. (Interview with Joseph Sisco by the authors).